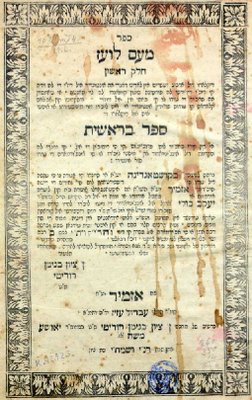

Rabbi Yaakov Culi 5449/1689-5492/1732

'It makes you feel like becoming a better Jew." '

This was the first reaction of a friend after examining several chapters of MeAm Loez, which I had recently begun to translate into English. His words did not surprise me. While working on the book, I too had felt tugs at my heartstrings, and I found myself saying blessings with more feeling, being just a bit more careful of my religious obligations. The sefer is indeed like a magnet, drawing a person closer to Torah.

For close to 200 years, MeAm Loez enjoyed unparalleled popularity among the common folk of Sephardic Jewry. A large and expensive set was often given as a gift to a new son-in-law, much as a Shas (set of the Talmud) is today. In many synagogues, the regular evening Torah-study session between Minchah and Maariv centered on this book, and a number of groups were formed for the express purpose of studying it. It is said that Rabbi Chaim Medini, famous as the author of the encyclopedic work Sedei Chemed, would join such groups, so greatly did he value its wisdom.

Nowadays MeAm Loez in Hebrew has become a popular Bar Mitzvah gift. Nevertheless, many yeshiva students seem to shun it, as part of a common prejudice against anything written in the vernacular - for the MeAm Loez was originally written in Ladino.

True enough, this work was specifically written for the common man. Far from talking down to the common man, however, the author uplifts the reader with a rich anthology of Torah thoughts from the Talmud, Midrash, Zohar, halachic literature, and philosophy, together with in-depth discussions and analysis.

The Author

The author of MeAm Loez, Rabbi Yaakov Culi, had enjoyed a reputation as one of the giants of his generation. He was born in Jerusalem in 1689 to Rabbi Machir Culi (1638-1728), a well-known scholar and saint who was a scion of one of the leading Jewish families of Crete (Candai). Crete had belonged to Venice, but in 1645 the Turks invaded this island and laid siege to its capital and chief cities. This siege lasted for twenty-five years, one of the longest in modern history, and resulted in almost two hundred thousand casualties.

When the Turks were finally victorious in 1689, the island's economy was in shambles, with the Jews suffering most of all. Fleeing with his remaining wealth, Rabbi Machir eventually settled in Jerusalem around 1688. Here he found a city of scholars, boasting such luminaries as Rabbi Chezkiel di Silva (author of Pri Chadash) and Rabbi Ephraim Navon (author of Machaneh Ephraim). Leading the community was Rabbi Moshe Galanti, who had been appointed as the first Rishon LeTzion, Chief Rabbi of the Sephardic Jews, in 1668. Rabbi Machir was drawn to another prominent sage, Rabbi Moshe ibn Chabib, and soon married his daughter.

Their first son, Yaakov, was born in 1689, a time of great upheaval in Jerusalem. It began with one of the worst famines in memory, causing many to flee to other locales. A second, even more severe blow to the Jewish community was the death of the illustrious Rabbi Moshe Galanti. This Torah giant had been the undisputed leader for twenty years, and his passing left a great void in the community. His place was filled by Rabbi Yaakov's maternal grandfather, Rabbi Moshe ibn Chabib.

His Grandfather's Legacy

As a child, Rabbi Yaakov showed great promise, rapidly gaining reputation as a prodigy. He was raised on his grandfather's knee, and by his sixth year was questioning some of his Talmudic interpretations. Although he was only seven when Rabbi Moshe ibn Chabib died, the memory of his grandfather deeply impressed him for the rest of his life.

A year later, tragedy struck again when his mother died. His father soon remarried and the family moved to Hebron, and then to Safed. Here the young genius advanced rapidly in his studies, and began the major task of editing his grandfather's numerous writings. Probing his father and other local rabbis for information, he became aware of the gigantic stature of Rabbi Moshe ibn Chabib.

Among the things that he learned was that his grandfather had been born in Salonica in 1654, descending from a famed family with origins in Spain. Among his ancestors were Rabbi Yosef Chabiba (circa 1400) - the Nimukei Yosef, and Rabbi Yaakov ibn Chabib (1459-1516) - the Ein Yaakov. His grandfather had lived in Constantinople for a while, and then came to Jerusalem at the age of sixteen. In 1688, when but thirty-four, he was appointed head of the great Yeshiva founded by Moshe ibn Yeush, a philanthropist friend from Constantinople. When Rabbi Moshe ibn Chabib died at 42, he had already earned a reputation as one of the greatest sages of his time.

The Constantinople Venture

Rabbi Yaakov was determined to publish his grandfather's works. Since adequate printing facilities did not exist in the Holy Land at the time, he went to Constantinople, where he had hoped to find financial backing for this task. He arrived in the capital of the Ottoman Empire in 1714.

A sensitive young man of 24, Rabbi Yaakov was aghast at conditions in Constantinople. True, the city had many sages who toiled day and night to uplift the community, as well as a great Kolel (institute of advanced study), known as The Hesger. But in general, community life was sinking. Constantinople had been a center of Shabbatai Tzvi's false Messianic movement, and more than any other city, it had suffered from this heretical spirit. Jewish education was virtually nonexistent, and most of the populace were barely literate in Hebrew. People did attend synagogues, but beyond this Jewish life was on the verge of total disintegration.

Winning support from a Chaim Alfandri, he began work on his grandfather's classical work Get Pashut, a profound treatment of the extremely complex laws governing Jewish divorce. This was finally printed by Yitzchak Alfandri, a relative of Chaim, in 1719 in Ortokoi, a suburb of Constantinople. (The only other sefer I know of published in Ortokoi is Bnei Chayay, in 1717.)

Disciple of the "Mishneh LaMelech"

At this time, the undisputed leader of Sephardic Jewry was Constantinople's Chief Rabbi, Rabbi Yehuda Rosanes (1658- 1727). He learned of the brilliant scholar who had come to town, and before long, had appointed him to his bais din (rabbinical court) - no mean accomplishment for so young a man. Rabbi Yaakov Culi soon became the prime disciple of this leader of world Jewry.

Rabbi Yaakov had just finished printing his grandfather's Shemos BeAretz, when tragedy struck the Jewish community. His great master, Rabbi Yehuda Rosanes, passed away on 22 Nissan (April 13), 1727. During the mourning period, the sage's house was looted, and a number of his manuscripts were stolen. The rest were left in a shambles, scattered all over the house. Assuming authority rare for a man of his youth, Rabbi Yaakov Culi undertook the responsibility of reassembling these important writings and editing them for publication.

During the first year, he completed work on Perushas Derachim, a collection of Rabbi Yehuda's homilies. In his introduction to this book, Rabbi Yaakov Culi mourns the loss of his great master...But his main work had just begun: Rabbi Yehuda had left one of the most significant commentaries ever written on the Rambam's Mishneh Torah, the monumental Mishneh LaMelech.

Rabbi Yaakov spent three years carefully assembling and editing this manuscript. Contemporary scholars struggle through the lengthy, profound sequences of logic found in this commentary; to be sure, the editor was in perfect command of every one of these discussions. Where certain points were ambiguous, or where additional explanations were required, Rabbi Yaakov added his own comments in brackets. In 1731, the work was completed and printed as a separate volume. Just eight years later, it was reprinted with the Mishneh Torah - below the Rambam's text, on the same page - one of a half dozen commentaries accorded this singular distinction.

Today, the Mishneh LaMelech is included in all major editions of the Rambam's code. Studying it, one also sees Rabbi Yaakov Culi's bracketed commentaries and notes. At the beginning of every printed Rambam, one can find his introduction to this work. Thus, at the age of forty, he had already won renown as a leading scholar of his time.

His Own Life Work

Having completed the publication of the works of both his grandfather and his master, Rabbi Yaakov began to search for a project that would be his own life work. There is no question that he could have chosen to write a most profound scholarly work, joining the ranks of so many of his contemporaries. Instead, he decided to write a commentary on the Torah for the unlettered Jew. As he writes in his preface: This might strike many of his colleagues as strange. Why would he, a scholar of the first water, write a work for the masses? Surely, one of his stature should address himself to the scholarly community. But apparently he was otherwise motivated: How could he engage in scholarship when he saw Jewish life disintegrating all around him? How could he close his eyes to the thousands of souls, crying out for access to the Torah?

Ladino - The Language of his Work

As his vehicle of expression, Rabbi Yaakov chose Ladino, the common language spoken by Sephardic Jews. Ladino is to Spanish as Yiddish is to German. Written with Hebrew letters, it looks very strange to the untrained eye; but with a little experience and a good Spanish dictionary, it rapidly becomes comprehensible.

Ladino was developed among the Jews of Spain. As long as the Jewish community flourished there, Ladino was written with the Spanish alphabet, with a liberal sprinkling of Hebrew thrown in. In concept, it was not very different from the language used in much of today's Torah literature, where Hebrew is intermingled with English.

After the Jews were expelled from Spain, they gradually dropped use of the Spanish alphabet, and began writing Ladino with Hebrew letters, which they knew from their prayers. At first there was no literature in this language; it was used primarily in correspondence and business records. The first books in Ladino appeared in Constantinople - a translation of the Psalms in 1540, and one of the Torah in 1547. A few years later, the first original work was published in this language, Regimiento de la Vida (Regimen of Life), by Rabbi Moshe Almosnino.

While a few other classics, such as Chovos HaLevavos (Duties of the Heart) and the Shulchan Aruch had been translated into Ladino, the amount of Torah literature available to those who did not understand Hebrew was extremely sparse. It was this vacuum that Rabbi Yaakov Culi decided to fill. As he points out, even such major works as the Rambam's Commentary to the Mishnah, and Saadiah Gaon's Emunos VeDayos (Doctrines and Beliefs) had been written in Arabic, the vernacular in their time. But no work of this scope had ever been attempted in the vernacular.

The Scope of "MeAm Loez"

What Rabbi Yaakov had planned was nothing less than a commentary on the entire Bible, explaining it from countless approaches. Where the Scripture touched on practical application of the Law, it would be discussed in length, with all pertinent details needed for its proper fulfillment. Thus, for example, when dealing with the verse "Be fruitful and multiply", the author devotes some fifty pages to a discussion of the laws of marriage, including one of the clearest elucidations of the rules of family purity ever published in any language.

Then, as now, considerable money could be gained in publishing a successful book. Here the saintliness of the author comes to the fore. In a written contract, he specified that all the profits realized from sales of the book were to be distributed to the yeshivos in the Holy Land, as well as the Hesger Kolel in Constantinople. He would only retain for himself the standard commission given to charity collectors.

The work was originally planned to consist of seven volumes, encompassing all the books of the Bible. In the two years that the author worked on it, he completed all of the book of Genesis (Bereishit), and two-thirds of Exodus (Shemot), a total of over eleven hundred large printed pages. (In the current Hebrew translation, this fills over 1800 pages.) Then, at the age of 42, on 19 Av (August 9), 1732, Rabbi Yaakov Culi passed away, leaving his work unfinished.

The contemporary Sephardic sages saw the strong positive effect MeAm Loez was having on the community, and thus sought others to complete the work. Rabbi Yaakov had left over voluminous notes, and these would be incorporated into the continuation. The first one to take on this task was Rabbi Yitzchak Magriso, who completed Exodus in 1746, Leviticus in 1753, and Numbers in 1764. Deuteronomy was finished by Rabbi Yitzchak Bechor Agruiti in 1772. These latter sages followed Rabbi Culi's style so closely, that the entire set can be considered a single integral work.

Never before had a work achieved such instant popularity. But even greater than its popularity was its impact. Thousands of readers who had been almost totally irreligious suddenly started to become observant. A new spirit swept through Sephardic communities, similar to that engendered by the Chassidic movement in Eastern Europe a half century later. Very few sefarim in modern times have had such a great impact on their milieu.

Reprints and Translations

The MeAm Loez was reprinted at least eight times, in cities around the Mediterranean region. The volumes were so heavily used, that few copies of the older editions are existent - they were literally worn out, just like a Siddur or Chumash. An Arabic translation published under the name of Pis'shagen HaKasav, was prepared by Rabbi Avraham Lersi, and was published in various cities in North Africa between 1886 and 1904. An edition of Bereishit, transliterated into Spanish letters, was published in 1967 by the Ibn Tibbon Institute at the University of Grenada, Spain.

Although this was one of the most popular volumes in Sephardic countries, it had been virtually unknown to Ashkenazim, who generally do not read Ladino. With the destruction of most Ladino-speaking communities in World War 11, the number of people who could read the MeAm Loez in the original diminished. Translation of the entire set into Hebrew in the late 1960's finally brought it to the attention of the contemporary Torah world. Although the original name of the Sefer was MeAm Loez, in the Hebrew edition the word "Yalkut" (Anthology) was added. One reason for this was the fact that certain portions, which the translator felt were not pertinent to our times, were omitted.

In naming his work, Rabbi Yaakov Culi based the title on the verse, "When Israel went out of Egypt, the house of Jacob from a strange-speaking people (MeAm Loez), Yehudah became His holy one, Israel His kingdom" (Psalms 114:l). Through the medium of this book, he had hoped that his people would emerge from the shackles of ignorance. Yehudah in Rabbi Culi's reference alludes to Yehudah Mizrach, a Constantinople philanthropist, who underwrote the costs of the printing of the first edition. His reference to the last phrase in this verse was then meant to be a prayer that this work would bring Israel to once again become part of "His kingdom."

He succeeded, perhaps beyond his fondest dreams. A half-century after his death, Rabbi Chaim Yosef David Azzulai (the Chida) wrote of him, "He was expert in the Talmud, codes and commentaries, as we can readily see from his book MeAm Loez, which he wrote to bring merit to the multitudes. Fortunate is he and fortunate is his portion."

No comments:

Post a Comment