PRESENÇA JUDAICA NA LÍNGUA PORTUGUESA EXPRESSÕES E DIZERES POPULARES EM PORTUGUÊS DE ORIGEM CRISTÃ-NOVA OU MARRANA

PRESENÇA JUDAICA NA LÍNGUA PORTUGUESA EXPRESSÕES E DIZERES POPULARES EM PORTUGUÊS DE ORIGEM CRISTÃ-NOVA OU MARRANA

Jane Bichmacher de Glasman (UERJ)

O objetivo do presente trabalho é apresentar alguns exemplos de influência judaica na língua portuguesa, a partir de uma ampla pesquisa sócio-lingüística que venho desenvolvendo há anos. A opção por judaica (e não hebraica) deve-se a uma perspectiva filológica e histórica mais abrangente, englobando dialetos e idiomas judaicos, como o ladino (judeu-espanhol) e o iídiche (alemão), entre os mais conhecidos, além de vocábulos judaicos e expressões hebraicas que passaram a integrar o vernáculo a partir de subterfúgios e/ ou corruptelas, cuja origem remonta à bagagem cultural de colonizadores judeus, cristãos-novos e marranos.

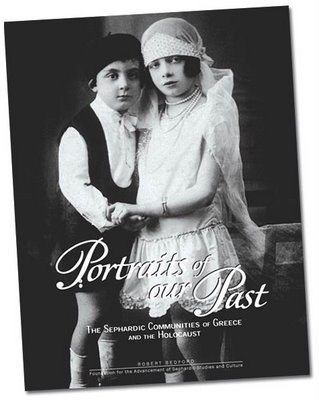

Há uma significativa probabilidade estatística de brasileiros descendentes de ibéricos, principalmente portugueses, terem alguma ancestralidade judaica. A base histórica para tal é a imigração maciça de judeus expulsos da Espanha, em 1492, para Portugal, devido à contigüidade geográfica e às promessas (não cumpridas) do Rei D. Manuel I, que traziam esperança de sua sobrevivência judaica como tal. Mesmo com a expulsão de Portugal em 1497, os judeus (além dos cristãos-novos e dos cripto-judeus ou marranos) chegaram a constituir 20 a 25% da população local.

Sefaradim (de Sefarad, Espanha, da Península Ibérica) procuraram refúgio em países próximos no Mediterrâneo, norte da África, Holanda e nas recém-descobertas terras de além-mar nas Américas, procurando escapar da Inquisição. Até hoje é controversa a origem judaica ou criptojudaica de descobridores e colonizadores do Brasil, para onde imigraram incontáveis cristãos-novos, alternando durante séculos uma vida como judeus assumidos e marranos, praticando o judaísmo secretamente (fora os que permaneceram efetivamente católicos), de acordo com os ventos políticos, sob o domínio holandês ou a atuação da Inquisição, variando de um clima de maior tolerância e liberdade à total intolerância e repressão.

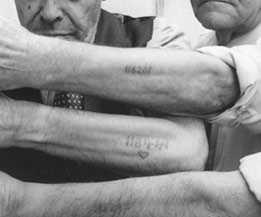

Comparando apenas sob o ponto de vista cronológico, nem sempre lembramos que, enquanto o Holocausto na Segunda Guerra Mundial foi tão devastador, especialmente nos quatro anos de extermínio maciço de judeus, a Inquisição durou séculos, pelo menos três dos cinco da história “oficial” do Brasil, isto é, após o descobrimento. Tantos séculos de medo, denúncias, processos e mortes, geraram, por um lado, um ambiente psicológico de terror para os judeus e cristãos novos no Brasil; por outro, um anti-semitismo evidente ou subliminar que permaneceu arraigado na população, inclusive como autodefesa e proteção.

Uma característica do comportamento de cristãos-novos “suspeitos” foi procurar ser “mais católicos do que os católicos”, buscando sobreviver à intolerância e determinando práticas sócio-culturais e lingüísticas.

A citada alternância entre vidas assumidamente judaicas e marranas, praticando judaísmo em segredo, com costumes variados, unificados pela “camuflagem” de seu teor judaico, gerou comportamentos e aspectos culturais (abrangendo rituais, superstições, ditados populares, etc.) que se arraigaram à cultura nacional. A maioria da população desconhece que muitos costumes e dizeres que fazem parte da cultura brasileira têm sua origem em práticas criptojudaicas. Apresentarei alguns exemplos bem como suas origens e explicações, a partir da origem judaica

“marrana”.“Gente da nação” é uma das denominações para designar marranos, judeus, cristãos-novos e cripto-judeus, embora existam diferenças entre termos e personagens.

Cristãos-novos foi denominação dada aos judeus que se converteram em massa na Península Ibérica nos séculos XIII e XIV; é preconceituosa devido à distinção feita entre os mesmos e os “cristãos-velhos”, concretizado nas leis espanholas discriminatórias de “Limpieza de Sangre” do século XV.

Criptojudeus eram os cristãos-novos que mantiveram secretamente seu judaísmo. Gente da nação era a expressão mais utilizada pela Inquisição e Marranos, como ficaram mais conhecidos. Embora todos fossem descendentes de judeus, só poucos voltaram a sê-lo, e em países e épocas que o permitiram.

O próprio termo

“marrano” possui uma etimologia diversificada e antitética. Unterman (1992: 166), conceitua de forma tradicional, como “nome em espanhol para judeus convertidos ao cristianismo que se mantiveram secretamente ligados ao judaísmo. A palavra tem conotação pejorativa” geralmente aplicada a todos os cripto-judeus, particularmente aos de origem ibérica. Em 1391 houve uma maciça conversão forçada de judeus espanhóis, mas a maioria dos convertidos conservou sua fé. Já Cordeiro (1994), com base nas pesquisas de Maeso (1977), afirma que a tradução por “porco” em espanhol tornou-se secundária diante das várias interpretações existentes na histografia do marranismo.

Para o historiador Cecil Roth (1967), marrano, velho termo espanhol que data do início da Idade Média que significa porco, aplicado aos recém-convertidos (a princípio ironicamente devido à aversão judaica à carne de porco), tornou-se um termo geral de repúdio que no século XVI se estendeu e passou a todas as línguas da Europa ocidental.

A designação expressa a profundidade do ódio que o espanhol comum sentia pelos conversos com quem conviviam. Seu uso constante e cotidiano carregado de preconceito turvou o significado original do vocábulo. Em “Santa Inquisição: terror e linguagem”, Lipiner (1977) apresenta as definições: “Marranos: As derivações mais remotas e mais aceitáveis sugerem a origem hebraica ou aramaica do termo.

Mumar: converso, apóstata. Da raiz hebraica

mumar, acrescida do sufixo castelhano ano derivou a forma composta mumrrano, abreviado: Marrano. Tratar-se-ia, pois de um vocábulo hebraico acomodado às línguas ibéricas.

Marit-áyin: aparência, ou seja, cristão apenas na aparência.

Mar-anús: homem batizado à força.

Mumar-anus: convertido à força. Contração dos dois termos hebraicos, mediante a eliminação da primeira sílaba”.

Anus, em hebraico, significa forçado, violentado.

Antes de exemplificar a contribuição lingüística marrana, convém ressaltar que a vinda dos portugueses para o Brasil trouxe consigo todos os empréstimos culturais e lingüísticos que já haviam sido incorporados ao cotidiano ibérico, desde uma época anterior à Inquisição, além de novos hábitos e características; muitas palavras e expressões de origem hebraica foram incorporadas ao léxico da língua portuguesa mesmo antes de os portugueses chegarem ao Brasil. Elas encontram-se tão arraigadas em nosso idioma que muitas vezes têm sua origem confundida como sendo árabe ou grega. Exemplo: a “azeite”, comumente atribuída uma origem árabe por se assemelhar a um grande número de palavras começadas por “al-” (como alface, alfarrábio, etc.), identificadas como sendo de origem árabe por esta partícula corresponder ao artigo nesta língua. O artigo definido hebraico é a partícula “a-” e “azeite” significa, literalmente, em hebraico “a azeitona” (ha-zait).

Apesar da presença judaica por tantos séculos, em Portugal como no Brasil, as perseguições resultaram também em exclusões vocabulares. A maior parte dos hebraísmos chegou ao português por influência da linguagem religiosa, particularmente da Igreja Católica, fazendo escala no grego e no latim eclesiásticos, quase sempre relacionados a conceitos religiosos, exemplos:

aleluia, amém, bálsamo, cabala, éden, fariseu, hosana, jubileu, maná, messias, satanás, páscoa, querubim, rabino, sábado, serafim e muitos outros.

Algumas palavras adotaram outros significados, ainda que relacionados à idéia do texto bíblico. Exemplos:

babel indicando bagunça;

amém passando a qualquer concordância com desejos;

aleluia usada como interjeição de alívio.

O preconceito marca palavras originárias do hebraico usadas de forma depreciativa, como:

desmazelo (de mazal – negligência, desleixo),

malsim (de mashlin – delator, traidor),

zote (de zot / subterrâneo, inferior, parte de baixo – pateta, idiota, parvo, tolo), ou

tacanho (de katan – que tem pequena estatura, acanhado; pequeno; estúpido, avarento); além de palavras relacionadas a questões financeiras, como

cacife, derivada de kessef = dinheiro.

Dezenas de

nomes próprios têm origem hebraica bíblica, como: Adão, Abraão, Benjamim, Daniel, Davi, Débora, Elias, Ester, Gabriel, Hiram, Israel, Ismael, Isaque, Jacó, Jeremias, Jesus, João, Joaquim, José, Judite, Josué, Miguel, Natã, Rafael, Raquel, Marta, Maria, Rute, Salomão, Sara, Saul, Simão e tantos outros. Alguns destes, na verdade, são nomes aramaicos, oriundos da Mesopotâmia, como Abraão (Avraham), que se incorporaram ao léxico hebraico no início da formação do povo hebreu.

Podemos citar centenas de

nomes e sobrenomes de judaizantes e números de seus dossiês, desde a instalação da Inquisição no Brasil, a partir dos arquivos da Torre do Tombo, em Lisboa, e de livros como Wiznitzer (1966), Carvalho (1982), Falbel (1977), Novinsky (1983), Dines (1990), Cordeiro (1994), etc. Sobrenomes muito comuns, tanto no Brasil como em Portugal, podem ser atribuídos a uma origem sefardita, já que uma das características marcantes das conversões forçadas era a adoção de um novo nome. Muitos conversos adotaram nomes de plantas, animais, profissões, objetos, etc., e estes podem ser encontrados em famílias brasileiras, até hoje, em número tão grande que seria difícil enumerá-los. Exemplos: Alves, Carvalho, Duarte, Fernandes, Gonçalves, Lima, Silva, Silveira, Machado, Paiva, Miranda, Rocha, Santos, etc. Não devemos excluir a possibilidade da existência de outros sobrenomes portugueses de origem judaica.

Porém é importante ressaltar que não se pode afirmar que todo brasileiro cujo sobrenome conste dos processos seja descendente direto de judeus portugueses; para se ter certeza é necessária uma pesquisa profunda da árvore genealógica das famílias.

Há ainda algumas palavras e expressões oriundas do misticismo judaico, tão desenvolvido na idade média. O estudo do Talmud e da Cabalá trouxe também contribuições do aramaico, como a conhecida expressão

“abracadabra”, que é tida pela nossa cultura como uma “palavra mágica” (num sentido fabuloso), mas que, na realidade pode ser traduzida como “criarei à medida que falo” (num sentido real e sólido para a cultura judaica).

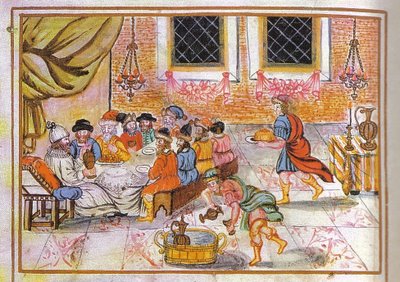

Algumas palavras também designam práticas judaicas ou formas de encobri-las, especialmente observável nos costumes alimentares. Por exemplo: os judeus são proibidos pela Torá de comer carne de porco, porque tem os cascos fendidos e não rumina, sendo, portanto, impuro. Para simular o abandono desse princípio e enganar espiões da Inquisição, os cristãos-novos inventaram as

alheiras, embutidos à base de carne de vitelo, pato, galinha, peru – e nada de porco. Após algumas horas de defumação já podem ser consumidos. Da mesma forma,

peixes “de couro” (sem escamas) não serviam para consumo.

Passando às expressões, apresento alguns exemplos, sua origem e explicação:

– “Ficar a ver navios” – Em 1492 foi determinado que os judeus que não se convertessem teriam de deixar a Espanha até ao fim de julho. Centenas de milhares então se fixaram em Portugal. O casamento do rei D. Manuel com D. Isabel, filha dos Reis Católicos, levou-o a aceitar a exigência espanhola de expulsar todos os judeus residentes em Portugal que não se convertessem ao catolicismo, num prazo que ia de Janeiro a Outubro de 1497. O rei Dom Manuel precisava dos judeus portugueses, pois eram toda a classe média e toda a mão-de-obra, além da influência intelectual. Se Portugal os expulsasse logo como fez a Espanha, o país passaria por uma crise terrível. Na realidade D. Manuel não tinha qualquer interesse em expulsar esta comunidade, que então constituía um destacado elemento de progresso nos setores da economia e das profissões liberais. A sua esperança era que, retendo os judeus no país, os seus descendentes pudessem eventualmente, como cristãos, atingir um maior grau de aculturação. Para obter os seus fins lançou mão de medidas extremamente drásticas, como ter ordenado que os filhos menores de 14 anos fossem tirados aos pais a fim de serem convertidos. Então fingiu marcar uma data de expulsão na Páscoa. Quando chegou a data do embarque dos que se recusavam a aceitar o catolicismo, alegou que não havia navios suficientes para os levar e determinou um batismo em massa dos que se tinham concentrado em Lisboa à espera de transporte para outros países. No dia marcado, estavam todos os judeus no porto esperando os navios que não vieram. Todos foram convertidos e batizados à força, em pé. Daí a expressão: “ficaram a ver navios”. O rei então declarou: não há mais judeus em Portugal, são todos cristãos (cristãos-novos). Muitos foram arrastados até a pia batismal pelas barbas ou pelos cabelos.

– “Pensar na morte da bezerra”: frase tão comumente dita por sertanejos quando querem referir-se a alguém que está meditando com ares de preocupação: “está pensando na morte da bezerra”. Registram as denunciações e as confissões feitas ao Santo Oficio, a noção popular, naquele distante período, do que seria o livro fundamental do judaísmo: a Torá. De

Torá veio

Toura e depois,

bezerra, havendo inclusive quem afirmasse ter visto em cara de alguns cristãos-novos, o citado objeto, com chifres e tudo.

– “Passar a mão na cabeça”, com o sentido de perdoar ou acobertar erro cometido por algum protegido, é memória da maneira judaica de abençoar de cristãos-novos, passando a mão pela cabeça e descendo pela face, enquanto pronunciava a bênção.

– Seridó, região no Rio Grande do Norte, tem seu nome originário da forma hebraica contraída: Refúgio dele. Porém, não é o que escreve Luís da Câmara Cascudo, indicando uma origem indígena do nome da região, de “ceri-toh”. Em hebraico, a palavra

Sarid significa sobrevivente. Acrescentando-se o sufixo

ó, temos a tradução sobrevivente dele. A variação

Serid, “o que escapou”, pode ser traduzido também por refúgio. Desse modo, a tradução para o nome seridó seria refúgio dele ou seus sobreviventes.

– Passar mel na boca: quando da circuncisão, o rabino passa mel na boca da criança para evitar o choro. Daí a origem da expressão: “Passar mel na boca de fulano”.

– Para o santo: o hábito sertanejo de, antes de beber, derramar uma parte do cálice, tem raízes no rito hebraico milenar de reservar, na festa de Pessach (Páscoa), um copo de vinho para o profeta Elias (representando o Messias que virá, anunciado pelo Profeta Elias).

– “Que massada!” –usada para se referir a uma tragédia ou contra-tempo, é uma alusão à fortaleza de Massada na região do Mar Morto, Israel, reduto de Zelotes, onde permaneceram anos resistindo às forças romanas após a destruição do Templo em 70 d.C., culminando com um suicídio coletivo para não se renderem, de acordo com relato do historiador Flávio Josefo.

– “Pagar siza” significando pagar imposto vem do hebraico e do aramaico (mas = imposto, em hebraico de misa, em aramaico).

– “Vestir a carapuça” ou

“a carapuça serve para ...” vem da Idade Média inquisitorial, quando judeus eram obrigados a usar chapéus pontudos (ou com três pontas) para serem identificados.

– “Fazer mesuras” origina-se na reverência à Mezuzá (pergaminho com versículos de DT.6, 4-9 e 11,13-21, afixado, dentro de caixas variadas, no batente direito das portas).

– "Deus te crie" após o espirro de alguém é uma herança judaica da frase Hayim Tovim, que pode ser traduzido como tenha uma boa vida.

– “Pedir a bênção” aos pais, ao sair e chegar em casa, é prática judaica que remonta à benção sacerdotal bíblica, com a qual pais abençoam os filhos, como no Shabat e no Ano Novo.

– “Entrar e sair pela mesma porta traz felicidade” bem como o costume de varrer a casa da porta para dentro, costume arraigado até os dias de hoje, para “não jogar a sorte fora” é uma camuflagem do respeito pela Mezuzá, afixada nos portais de entrada, bem como aos dias de faxina obrigatória religiosa judaica, como antes do Shabat (Sábado, dia santo de descanso semanal) e de Pessach.

– “Apontar estrelas faz crescer verrugas nos dedos” era a superstição que se contava às crianças para não serem vistas contando estrelas em público e denunciadas à Inquisição, pois o dia judaico começa no anoitecer do dia anterior, ao despontar das primeiras estrelas, dado necessário para identificar o início do Shabat e dos feriados judaicos.

Para concluir, gostaria de mencionar um tema polêmico decorrente deste intercâmbio cultural-religioso: sua influência no português, em vocábulos que adquiriram uma conotação pejorativa e negativa. Os mais discutidos são:

judeu, significando usurário, o verbo

judiar (e o substantivo

judiação) com o sentido de maltratar, torturar, atormentar. Seja sua origem a prática de “judaizar” (cristãos-novos mantendo judaísmo em segredo e/ ou divulgando-o a outros), seja como referência ao maltrato e às perseguições sofridas pelos judeus durante a Inquisição, o fato é que, sem dúvidas, sua conotação é negativa, e cabe a nós estudiosos do assunto e vítimas do preconceito, esclarecer a população e a mídia, alertando e visando à erradicação deste uso, não só pelo desgastado “politicamente correto”, que leva a certos exageros, mas para uma conscientização do eco subliminar de um longo passado recente, Pelo qual não basta o pedido de perdão, se não conduzir a uma mudança no comportamento social.

Referências Bibliográficas

CARVALHO, Flávio Mendes de. Raízes judaicas no Brasil. São Paulo: Arcádia, 1982.

CORDEIRO, Hélio Daniel. Os marranos e a diáspora sefaradita. São Paulo: Israel, 1994.

DINES, Alberto. Vínculos do fogo. São Paulo: Cia. das Letras. 1990.

FALBEL, Nachman & GUINSBURG, Jacó. (org.) Os marranos. São Paulo: CEJ; USP, 1977.

GONSALVES DE MELLO, José Antonio. Gente da Nação In: Revista do Instituto Arqueológico, Histórico e Geográfico Pernambucano. 1979.

HOLANDA FERREIRA, Aurélio Buarque de. Novo dicionário da língua portuguesa. Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira, 1986.

HOUAISS, Antonio. Dicionário Houaiss da língua portuguesa. Rio de Janeiro: Objetiva, 2001.

LIPINER, Elias. Santa inquisição: Terror e linguagem. Rio de Janeiro. Documentário, 1977.

MAESO, David Gonzalo. A respeito da etimologia do vocábulo ‘marrano’. São Paulo, CEJ, 1977.

NOVINSKY, Anita. A inquisição. São Paulo: Brasiliense, 1983.

ROTH, Cecil (ed.) Enciclopédia judaica. Rio de Janeiro. Tradição, 1967.

UNTERMAN, Alan. Dicionário judaico de lendas e tradições. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 1992.

WIZNITZER, Arnold. Os judeus no Brasil Colonial. São Paulo: Pioneira, 1966.

(the blue strings are "Kedusha- Kever" strings wrapped around the site)

(the blue strings are "Kedusha- Kever" strings wrapped around the site)